Why Capturing Maduro Solves Nothing

The dramatic arrest looks decisive, but history shows foreign regime change often traps Washington inside instability it cannot control.

The third day of 2026 isn’t even over and Washington has already told the world what kind of year it intends to have.

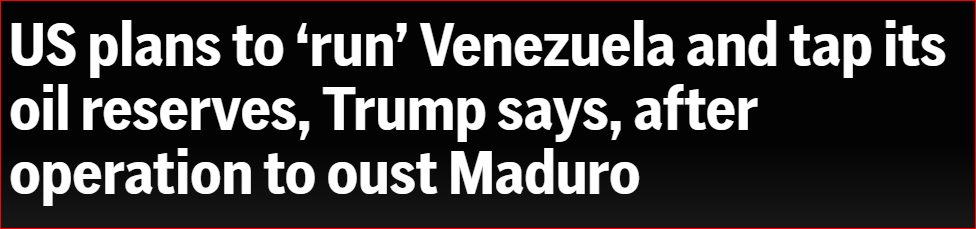

In a pre-dawn operation, US special forces struck Caracas, seized President Nicolás Maduro, and shipped him off to New York to face narcoterrorism charges. Within hours, Donald Trump was on camera boasting that the United States would “run Venezuela” for a while and take charge of its oil industry.

On the surface, it looks like a clean, dramatic victory: a dictator removed, no obvious US casualties, footage of celebrating exiles in Miami and Madrid, and a president basking in the glow of a daring military raid.

But if you step back from the images and think about what comes next, the whole thing has the feel of George W. Bush under the “Mission Accomplished” banner in 2003—or, further back, of George H. W. Bush sending troops into Panama to snatch Manuel Noriega. Back then, the operation to capture a foreign leader also ended with that leader on a plane to the United States and a White House convinced it had “solved” a problem.

The Panama template—a quick decapitation, a friendly government, and a legal fig leaf in US courts—is clearly in the minds of today’s planners. But Panama is a small country where the United States already had military bases and deep penetration into the security services. Even there, hundreds of Panamanians died and the invasion was condemned by the UN General Assembly as a violation of international law.

Venezuela is different in almost every way that matters: bigger landmass, far more people, far more weapons in private hands, and no standing US garrison. That alone should make anyone cautious about glib talk of “running” the country.

Internationally, the legal picture is as grim as the strategic one. The UN Secretary-General has warned that Washington’s action sets a “dangerous precedent,” and the Security Council is being hauled into emergency session at the request of Colombia with backing from Russia and China.

Legal scholars are already pointing out the obvious: snatching the sitting president of a sovereign state you’re not formally at war with, without Security Council approval and without a credible, imminent self-defense claim, runs straight into the prohibition on the use of force in Article 2(4) of the UN Charter.

Many are calling it what it looks like: an illegal act of aggression dressed up in narcoterrorism rhetoric.

Underneath the speeches and the talking points lies a childishly simple picture of world politics: somewhere out there is a “bad man.” Remove him, and the problem disappears. That story was told about Iran’s Mossadegh, Panama’s Noriega, Iraq’s Saddam Hussein, and Libya’s Gaddafi. Each time, removing the individual did nothing to resolve the underlying conflicts, and often made them worse.

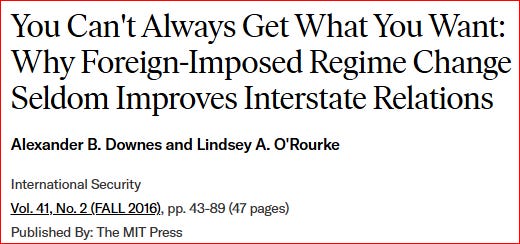

Political science backs up what common sense already suggests. Studies of “foreign‐imposed regime change” show that when outside powers topple a government, they rarely produce stable democracies. More often they bequeath weak institutions, civil wars, or long-running insurgencies that drag on for years after the invading power has declared victory.

The problem isn’t just that outsiders don’t understand local politics; it’s that power and violence inside a country do not reside in one man’s office. They are spread across parties, security services, militias, and business elites.

Treating Maduro as the sole problem—a cartoon villain who can be plucked out like a bad tooth—ignores the fact that he still had a social base, that opposition forces are fragmented, and that Venezuela’s political economy has been deformed by years of sanctions and corruption. Knock out the top piece of that structure without building something credible in its place and you don’t get order. You get a scramble.

If Venezuela falls apart, it will not necessarily resemble a classic civil war with neat front lines. A more plausible scenario is something uglier and more nebulous: a domestic insurgency that coexists with a nominal central authority installed under US protection.

Venezuela is heavily armed. Years of political polarization, along with an expanded role for security forces and pro-government colectivos, mean that weapons and combat experience are not in short supply. The country’s borders are long, porous and already used by guerrillas, paramilitaries, and criminal networks.

To see what that might look like in practice, you don’t have to speculate; you can look next door. Colombia’s armed conflict, officially dating from 1964, pitted the state against FARC, ELN, and a web of paramilitary and criminal actors for decades. It persisted, in part, because armed groups could slip across borders, find safe havens, move contraband, and restock. Even with massive US funding under Plan Colombia and repeated “final” offensives, the state never achieved a clean victory; violence simply changed shape.

Translate that pattern into a post-Maduro Venezuela run in practice by US–backed figures, and you can sketch the basic dynamic. There will be bombings of police stations and government offices, high-profile assassinations, and attacks on oil infrastructure. Kidnapping Americans or US contractors will become a lucrative tactic. Armed groups will drift across the Colombian and Brazilian borders and into the jungle or mountains when pressure grows.

Why take such a risk? Oil sits at the center of the answer.